Since signing up for the Affordable Connection Program last year, Myrna Broncho’s internet bill has been paid in full by the discount. The program offered $75 rebates for Internet access in tribal or high-cost areas like Broncho’s, but no cash.

Sarah Jane Tribble/KFF Health News

hide title

change the subtitles

Sarah Jane Tribble/KFF Health News

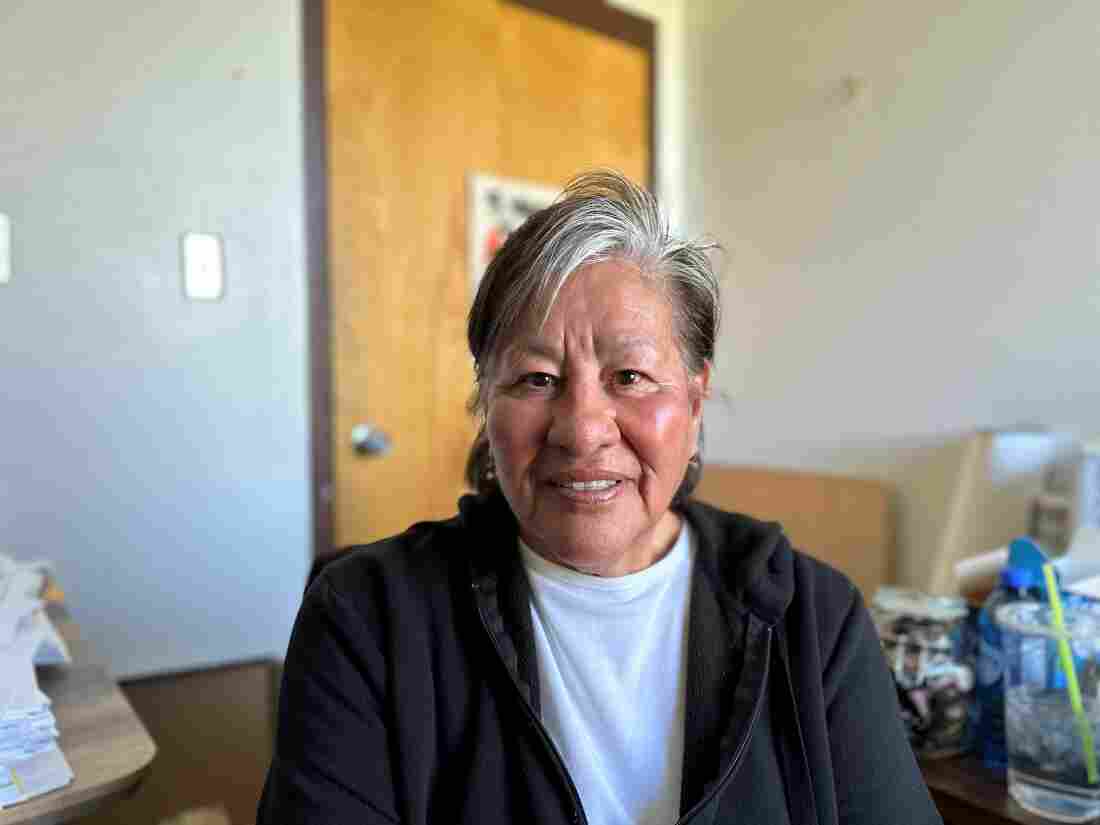

FORT HALL RESERVATION, Idaho – Myrna Broncho realized how necessary an Internet connection can be after she broke her leg.

In the fall of 2021, the 69-year-old climbed a ladder to the top of a shed in her pasture. The roof that protects her horses and cows had to be fixed. So, with drill in hand, she pushed down.

At that moment she slipped.

Broncho said her leg got caught between a pair of stairs as she fell, “and my bone was coming out and the only thing holding it up was my sock.”

Broncho crawled back into her house to get her phone. She hadn’t thought to take it with her because, she said, “I’ve never dealt with phones.”

Broncho needed nine surgeries and months of rehabilitation. Her hospital was more than two hours away in Salt Lake City, and her Internet connection at home was vital for her to keep notes and appointments, as well as communicate with her medical staff.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, federal lawmakers launched the Affordable Connection Program with the goal of connecting more people to their jobs, schools and doctors. More than 23 million low-income families, including Broncho’s, eventually signed up. The program provided $30 in monthly subsidies for internet bills, or $75 in discounts in tribal or high-cost areas like Broncho’s.

Now, ACP is out of money.

Myrna Broncho lives on the Fort Hall Reservation in rural southeastern Idaho on Broncho Road, which is named after her family. Broncho enrolled in the federal Affordable Connection Program, which offered discounted Internet service. “I like it,” she says, but the program is ending.

Sarah Jane Tribble/KFF Health News

hide title

change the subtitles

Sarah Jane Tribble/KFF Health News

In early May, Sen. John Thune (RS.D.) challenged an effort to continue funding the program, saying during a Commerce Committee hearing that the program needed to be renewed.

“As currently designed, ACP does a poor job of directing support to those who really need it,” Thune said, adding that many people who already had Internet access used the subsidies.

There has been a flurry of activity on Capitol Hill, with lawmakers initially trying and failing to attach funding to reauthorize the Federal Aviation Administration. Then Sen. Peter Welch (D-Vt.) traveled to his home state to tell constituents in the tiny White River crossing that Congress was still working toward a solution.

As the program’s funding was cut, both Democrats and Republicans sought new legislative action with proposals that sought to address concerns like those raised by Thune.

On May 31, when the program ended, President Joe Biden’s administration continued to call on Congress to take action. Meanwhile, the administration announced that more than a dozen companies — including AT&T, Verizon and Comcast — would offer low-cost plans to ACP enrollees, and the administration said those plans could affect up to 10 million households.

According to a survey of participants released by the Federal Communications Commission, more than two-thirds of households had unstable or no Internet connections before enrolling in the program.

Broncho had an Internet connection before the subsidy, but on this reservation in rural southeastern Idaho where she lives, about 40% of the 200 families enrolled in the program did not have Internet before the subsidy.

Nationwide, about 67% of non-urban residents reported having a broadband connection at home, compared with nearly 80% of urban residents, said John Horrigan, a national expert on technology adoption and senior fellow at the Benton Institute for Broadband and Society. Horrigan reviewed data collected from a 2022 Census study.

The FCC said on May 31 that the termination of the program will affect about 3.4 million rural households and more than 300,000 households in tribal areas.

The end of federal subsidies for Internet bills will mean “many families will have to make the difficult choice to no longer have Internet,” said Amber Hastings, an AmeriCorps member serving the Shoshone-Bannock tribes on the reservation. Some of Hastings’ enrolled families had to agree to a plan to pay off past due bills before joining the program. “So they were already in a tough spot,” Hastings said.

Matthew Rantanen, director of technology for the Southern California Tribal Chiefs Association, said the ACP was “extremely valuable.”

“Society has converted everything to the Internet. You can’t be in this society, as a member of society, and operate without a broadband connection,” Rantanen said. The disconnect, he said, puts indigenous communities and someone like Myrna at a disadvantage.

Rantanen, who advises tribes around the country on building broadband infrastructure on their land, said the benefits of ACP subsidies were twofold: They helped individuals get connected and encouraged providers to build infrastructure.

“You can guarantee a return on investment,” he said, explaining that the subsidies ensured that customers could pay for Internet service.

Since Broncho signed up for the program last year, her internet bill has been paid in full by the discount.

Broncho used the money she had previously budgeted for her internet bill to pay off credit card debt and a loan she took out to pay for her mother and brother’s headstones.

Since ACP funds ran out, the program only distributed partial subsidies. So, in May, Broncho received a bill for $46.70. In June, she expected to pay the full cost.

When asked if she would keep her Internet connection without the subsidy, Broncho said, “I’ll try.” She then added, “I’ll have to” even if it means getting a smaller serving.

Broncho said she uses the Internet for shopping, watching shows, banking and health care.

The Internet, Broncho said, is “a must.”

KFF Health News is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues and is one of the main operating programs in KFF — an independent source for research, polling and health policy journalism.

#Broadband #subsidies #rural #Americans #putting #telehealth #risk

Image Source : www.npr.org